The motivation to study the systemic sustainability potential of specifically two downstream solutions, plastics recycling and marine macroplastic cleanup, roots in the scientific and media discourse that surged in the mid-2010’s. Firstly, literature on plastic pollution begun exponentially has generally increasing around2015, most studies however focusing on marine microplastics. The increasing scientific knowledge on the impacts on marine plastic pollution sparked public awareness of the issue, resulting in an influx of new cleanup technologies and a heightened discussion on marine litter cleanup’s’ credibility as an effective strategy to combat the issue. Further, in 2018, the global recycling value chains were distorted by the world’s then largest importer of plastic waste, China, banning all imports of scrap plastics, causing plastic waste to pile up in net-exporting countries, including Norway. Thus, both plastics recycling and marine litter cleanup were challenged with respect to their credibility as effective strategies to combat plastic pollution.

The complexity of evaluating the level of circularity and sustainability impacts of these seemingly circular solutions to plastic pollution lead to the development of the industrial PhD project presented below. This summary of the project describes the state-of-the-art on plastic pollution, the scope of the study and research questions, the applied theoretical frameweok and research design, and finally, the results and main research contributions.

Knowledge on plastic pollution

Plastic production has been exponentially increasing since the 1950’s, growing on average 8.4% annually (De Costa et al. 2020). Most plastics still exist on the planet in some shape or form as only 9% of all plastics ever made have been recycled, 2% of which to materials of same or similar quality (Geyer et al. 2017). 12% have been incinerated and up to 79% have been landfilled or discarded into the environment (ibid). The high rate of plastic waste mismanagement has resulted in one of the major environmental catastrophes of our time, marine plastic pollution. An estimated 19-23 Mt of plastics leaked into the aquatic systems in 2016, and in a business-as-usual scenario, this leakage could reach 90 Mt per year by 2030 (Borrelle et al. 2020).

Up to 95% of all marine litter consists of plastic materials, single-use plastics being the most common type of coastal marine litter and fishing gear being the most common marine litter fraction found on the seafloor and observed as floating marine litter (Galgani et al. 2015). Abandoned, lost or otherwise discarded fishing gear (ALDFG) is also the most harmful type of marine litter due to ghost fishing (Deshpande et al. 2020). The environmental impacts of plastic marine litter range from habitat destruction, entanglement, ingestion, to contributing to accumulation of chemicals and transfer of invasive species (Forrest et al. 2019). As a result, millions of animals of at least 700 species are killed and 1400 species are negatively impacted by plastic marine litter yearly (Roman et al. 2020).

While this PhD project focuses on marine plastic pollution, plastic pollution negatively impacts all corners of the Earth and has wide-ranging effects on human health. Currently, the long-term health impacts of plastics on humans are unknown. However, they are most certainly unevenly divided, the global south carrying most of the negative health impacts of mismanaged plastics (Helm et al. 2023).

Due to the severity and scale of the plastic pollution problem, a recent review estimates that the cost of not taking decisive and systemic action against plastic pollution could be twice as costly compared to the cost of action toward zero plastic pollution by 2040. Additionally, a report by UNEP (2023) concludes that the profitability of the current plastics economy is based on environmental, social and intergenerational injustice.

Call for solutions based on the waste hierarchy and circular economy principles

Literature on plastic pollution calls for solutions based on the waste hierarchy and circular economy principles, along the whole plastics life cycle. The waste hierarchy provides a simple overview over the preferred prioritization of solutions, where the circular, product-based solutions are most preferred, the waste-focused, linear solutions are least preferred.

Figure 1. The waste hierarchy, divided into product-based and waste-based strategies (Havas 2024).

Unfortunately, the current plastics economy is fragmented, little transparent and highly linear. In contrast, according to the circularity principles, the plastics value chains should be slower, narrower, closed and regenerative.

Figure 2. The principles of circular economy (Konietzko et al. 2020).

Therefore, the scientific community has for years been calling for science-based systemic policies, as the existing policy frameworks do not match the severity and scale of the plastic pollution problem. This call was answered by the United Nations’ member states that agreed to forge a binding, global treaty to end plastic pollution by 2040 in March 2022. The aim of the treaty is to address the full life cycle of plastics, from production to responsible waste management. The treaty is currently being negotiated by the Intergovernmental Negotiation Committee, as the fifth and final, planned cycle of negotiations failed to provide an outcome all members could agree on in late November 2024. The expectations of the systemic impacts of the possible treaty are still high, but there are concerns of vested interests steering the negotiation process.

Systems thinking unlocks the sustainability potential of circular systems

The overarching research question (RQ) of this PhD study asks “how can the sustainability of downstream solutions to macroplastic pollution be improved by applying systems thinking?”. This RQ is approached through the application of transformative and pragmatic worldviews, and three theoretical lenses of systems thinking, sustainability, and circular economy. In the thesis, I argue that the lack of systems thinking in the development of circular plastic value chains can result in e.g. environmental sustainability issues in other resource value chains (i.e. problem transfer). This is a theme I discuss further in the results section. Systems thinking can be described in various ways, one being that it is a belief system that accommodates for systemic change through policy and industry application to solve complex problems. In the thesis, systems thinking is used both as an underlying theme to answer the RQ, a theoretical framework, and a method of inquiry.

A core argument in the thesis is that all three theories, while being interlinked, are non-exclusive. As an example, circular economy is not sustainable by default, which again refers to the need for systems thinking to connect these two theories, both of which address resource scarcity from different aspects. Firstly, circular economies can be described as systems that offer cyclical alternatives to the take-make-dump, linear economic model that assumes that resources are abundant, easy to source and cheap to dispose of. Circular systems use less materials and energy, maintain products longer, reuse resources as many times as feasible, and choose regenerative production methods (figure 2). Sustainability on the other hand describes ecosystems’ potential of surviving in a similar state over time, while sustainable development views ecological persistence from a society’s point of view. It is also worth noting that the interpretation of these theories varies in literature and practice, but that they are increasingly being established through quantification and indices, such as those described in the Sustainable Development Goals and the Planetary Boundaries concept (figure 3).

Figure 3. The planetary boundaries. Plastics mismanagement impacts all boundaries, but plastic pollution is included in the 'novel entities' silo (Richardson et al. 2023).

How can the sustainability of downstream solutions to macroplastic pollution be improved by applying systems thinking?

This overarching RQ is answered through three sub-research questions (SRQs), each resulting in relevant publications, as listed in table 1 below.

The results’ section is divided according to the three SRQs, as described below.

How is scientific literature on plastic pollution positioned to guide the development of solutions to marine macroplastic pollution?

The first SRQ is answered through two studies, the first paper investigating the connection of sources to marine litter, to causes of littering, and the suggestions of relevant solutions within marine litter research. By using the discourse analysis method, an overview of the understanding of the problem was obtained, through the identification of four main storylines that differ somewhat in their description of the issue. Firstly, all four storylines agreed on that the main sources to marine litter are single-use plastics and fisheries related litter. While there was agreement on the main sources of litter, three storylines conflicted with respect to the underlying causes and solutions. These conflicting strategies reflect a lack of integration between disciplinary approaches, resulting in uncertainty of how to stop marine litter accumulation most effectively, and indicates of a young field of research. A fourth storyline was identified and assessed as compatible with the first three as it focuses on the need for further research. There were also two emerging storylines: product design according to circular economy principles, especially for fishing gear, and marine litter cleanup as a complementary strategy to prevention. The key take-aways from this paper are that there is space for more systems-level research to connect sources, causes, and solutions to marine litter, and that understanding the underlying causes is a key parameter for setting effective plastic policies, highlighting the need to move away from litter monitoring to studying why litter accumulates in the environment and how to most effectively reduce its influx and accumulation.

Figure 4. Visualization of the four main storylines and two emerging storylines (Havas et al. 2022a).

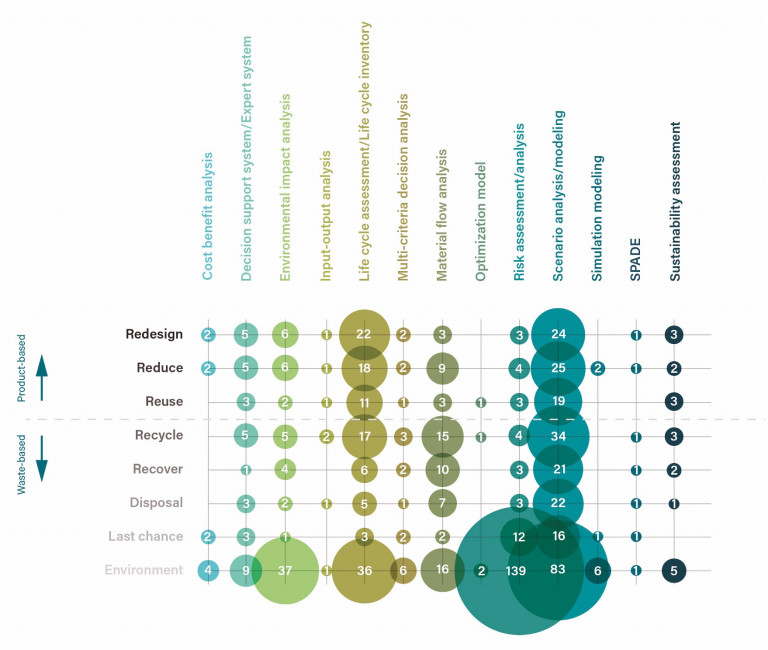

Further, the second paper related to the first SRQ studies how systems analysis tools are used in plastic pollution research and how systems-based literature might be positioned to guide the development of policies, such as the potential global treaty to end plastic pollution. We found that risk assessment, scenario modeling, environmental impact assessment, life cycle assessment, and material flow analyses account for 99% of the 18 techniques assessed. Only a third of publications focus on product-based solutions, the rest having a waste or litter focus. 97% of studies that specify plastic fraction focus on microplastics, while 13% include macroplastics as one of the studied fractions. Further, the lack of socio-cultural considerations in method use was also identified as a meaningful gap in application, together with the fact that no studies were completed in low-income (LI) countries. So, while systems analysis tools were found to offer great potential in guiding plastic policy allowing for the evaluation of complex problems to be analyzed in conjunction with solutions, they remain siloed un downstream application that focuses especially on microplastics in the marine environment and maintain a techno-centric view to problem solving.

Figure 5. The placement of the publications along the waste hierarchy and categorized according to method(s) used (Brooks and Havas, In review).

The two key recommendations for better science-for-policy production were made: firstly, there is a need for increased focus on the ‘emitter’ perspective, as opposed to the ‘receptor’ perspective. Secondly, a larger inclusion of knowledge from LI countries is needed to consider the historical inequalities between regions and to build trust and prioritize context-based needs.

Figure 6. The geographical allocation of publications (Brooks and Havas, In review).

The main research contributions from answering the SRQ1 are:

The usefulness of applying discourse analysis to identify possible source-cause-solution relationships in literature, and how these might impact policy.

Highlighting systems analysis as a suitable approach to studying plastic pollution. Especially with respect to creating science-for-policy.

Identification of various knowledge gaps in literature on marine litter and plastic pollution, considering specifically the systemic aspects of the plastic pollution problem.

How to address the circularity and sustainability challenges of macroplastics’ downstream management strategies?

The first publication, aiming to answer the SRQ2, studies the impact of physical distance in plastic waste recycling. In this study, it was found that exporting plastic waste from high-income (HI) to LI countries has negative feedback effects as it creates artificially clean environments in the exporting countries, thus supporting increasing plastic consumption, and as the environmental and social costs of plastic consumption are transported to the importing countries. As current circularity indicators used to measure e.g. the SDGs do not include these aspects when assessing plastics’ recycling rated, we suggest including physical distance as a circularity indicator and develop a concept around it, called ‘small circles’ (SC).

Figure 7. The visualization of the three steps included in the Small Circles concept (Havas et al. 2022b).

As shown in the figure X, in SC, waste management strategies are first rated according to the waste hierarchy within the country, the waste transport is penalized due to CO2 emissions, and waste management practices are rated again according to the waste hierarchy in the destination country. To investigate the practical feasibility of the SC, the end-of-life (EOL) circularity of commercial fishing gears deployed in Norway was studied. Firstly, the values describing the plastic waste management in the fishing sector (figure 8) were applied in the SC circularity indicator (figure 9).

Figure 8 and 9. The values considered in the Small Circles case study on Norwegian commercial fisheries' plastic waste management, and the explanation of the Circularity Indicator (Havas et al. 2022b).

The circularity indicator value was estimated to be much lower than the optimal value of 1, resulting in a key take-away from the case study: that there is potential to improve the recycling rates if the domestic recycling capacity was increased, including improved waste collection and segregation of valuable materials. However, the most common types of fishing gear used in fisheries in Norway are relatively heterogenous, requiring an analysis of the product-level EOL circularity potential. I conducted such an analysis to explore the need to adjust management strategies according to product-level variation when transitioning from linear to circular material management. This analysis was conducted using the Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) tool. Using MCDA, the six most used gears in commercial fishing in Norway were evaluated according to socioeconomic and environmental sustainability factors and based on the current technological capacity. It was found that features such as material composition and ease of transport played a major role in the gears’ potential of being managed according to circularity principles as shown in the figure 10 below.

Figure 10. The ranking of the Norwegian commercial fishing gears, with respect to their EOL circularity potential (Havas et al. 2024).

Purse seines scored high with respect to all three factors, as the gears can relatively easily be sorted and recycled to new materials, while longlines and traps/pots currently have no recycling alternatives as sorting materials for recycling requires extensive manual separation. The key take-away from this analysis is that fishing gears require customized management strategies to achieve EOL circularity, and in the study, concrete areas of improvement for specific gear types are described. These results can contribute to the development of more effective policies such as the upcoming extended producer responsibility (EPR) regulations from the EU that include fishing gear. Also, the results can provide value chain actors with tools for preparing and responding to relevant regulations.

Finally, the system impacts of cleanup technologies were evaluated, based in this dynamic model where it is assumed that the cost-effectiveness of marine litter cleanups is determined by the density and accessibility of litter. This again is impacted by the cleanup activity through reduction in the stock of litter. And thirdly, the risk of unintentional interaction with species and ecosystems that creates potential negative impacts, see figure 11.

Figure 11. Visualization of the three aspects to consider with respect to planning and implementing marine litter cleanups (Falk-Andersson et al. 2020).

Through a literature review conducted for this article, on the existing and planned technologies to clean litter from the sea surface, it was revealed that only a few technology developers were found to have considered the environmental impacts of their systems or estimated the potential density of litter in the areas they are planning to operate in. There seemed to be no clear sustainability standards for this emerging industry where cleanup systems vary in size and operational features and thus have also varying potential of impacts. Therefore, we recommend that cleanup system developers and regulators could learn from fisheries management by considering the basic management principles such as cost-per-unit-effort and the risk of catching ‘non-target species’. For example, by placing cleanup systems closer to source where densities are observed as high (such as highly polluted rivers) and considering seasonal changes in e.g., marine species’ emigrational patterns.

To conclude, the research contributions related to answering the SRQ2 are that:

Siloed approach to plastics management contributes to the pollution problem. Application of systems considerations to evaluate the net global sustainability of solutions to plastic pollution is necessary

Plastics recycling lacks transparency and traceability of materials. Thus, absent reporting regarding the management pathways of plastic waste should be punished.

Application of MCDA for complex management challenges. This method was found useful to determine a variety of factors that impact EOL FG management’s sustainability, as it allows for the standardization of qualitative and quantitative data and manages to consider a variety of alternatives.

Marine litter cleanup systems need industry sustainability standards, alike those applied to fisheries management. So., the adaptation of cost-per-unit considerations and avoidance of catching non-target species.

Policy’s role in accommodating for circularity

The third and final SRQ was answered through reflection of the research findings from the articles related to SRQ1 and 2, and discussed in a greater, circular economy context in three policy briefs.

Firstly, the background to these policy briefs relates to the urgency I experience as a holder of updated, scientific knowledge on a major societal issue to try to influence positive change. The boundaries between academia and the real world are changing, allowing for, and even expecting researchers to actively engage in public debates, below described by Yamin (2019) as “professionalism and impartiality not requiring us to be indifferent to the fate of the world”. Plastics is an increasingly politicized issue, and it is widely experienced, both in scientific and media discourses, as well as policy development processes, that vested interests aim to hinder policy development that could meaningfully limit plastic pollution. Especially in the light of the current plastics treaty negotiations, I argue that it is timely for researchers to engage in debated to counter vested interests’ lobbyism with scientific facts.

The policy aspect was present throughout the PhD project, resulting in three policy briefs where the urgency of accommodating for systems-based circularity was emphasized. In these publications, we encourage Europe and the US to take leadership in the development of circular economies to respond to and avoid crises, and to unlock environmental and economic benefits. These benefits are largely unknown, as are the risks of the linear models, displayed by marginal public and private investments in circularity. Stalling circular development could result in the losses of vast investments and millions of tons plastics mismanaged. To maintain the momentum around circular economy development and to avoid resource losses. A three-step playbook for a system change is recommended:

Create national goals combined with regulations to detach the value of recycled plastics from fossil fuel prices

Improve the economics of circular practice through well-designed EPR programs

Improve the transparency of value chains through global engagement and local solutions

The key take-away of the policy briefs can be described as: “Development of circular economies based on systemic sustainability and appropriately scoped life cycle analyses can be positive to the triple bottom line and allow us to ease back from ecological tipping points. So, rather than considering the transition to circularity as restrictive, systems thinking allows for policymakers to see the wide-ranging benefits of creating plastic value chains that are robust, flexible, and sustainable in the long-term”.

The main research contributions of answering the SRQ3 are the description of:

The paradox of treating circularity as a luxury - circular development should be prioritized as a strategic response to a multitude of risks, helping to respond to and avoid future crises.

Acknowledging the need for global and regional targets aligned with local conditions. Cooperation between stakeholders and data access at all levels of policy is needed to align global targets with local conditions and efforts.

Create robust and flexible value chains for plastics through EPR regulations and detach the value of recyclables from oil-and gas prices. Fiscal tools that support the establishment of markets for recycled plastics through the internalization of full costs of plastics’ life cycle can correct the market failures that are causing plastic pollution.

Should I answer the overall research question in one sentence, it would be this: “The sustainability of downstream solutions to marine macroplastic pollution can be improved by applying systems thinking if they are transparent in their net global sustainability contribution, supported by effective plastic policies, and treated as supplementary strategies to more effectual methods upstream”.

This thesis has left many questions unanswered, which is why I finish this summary with some research recommendations going forward. In general, systems-based tools should be applied widely to study plastic pollution, to avoid for example lock-in effects when solutions are scaled up. We also must be mindful of the socio-cultural aspects when developing solutions to the plastic pollution crisis to ensure a fair transition to circularity.

More specifically, there is a great opportunity to learn about the discourse dynamics within a society and how these might steer policy. The strengths and weaknesses of systems analysis techniques, with respect to for example their harmonization should be investigated, especially if they are being increasingly used to form policies and management strategies. And finally, as collected marine litter is a growing waste issue, more research should focus on how this fraction is managed, especially in countries where the problem is caused by poor waste management capacity in the first place,

- as we don't want to be going in circles, cleaning the same litter repeatedly, but to move forward, toward circularity.

All articles included in this PhD are available at The University of Aalborg`s website here.